Using ultrasound waves, MIT engineers have found a way to enhance the permeability of skin to drugs, making transdermal drug delivery more efficient. This technology could pave the way for noninvasive drug delivery or needle-free vaccinations, according to the researchers.

“This could be used for topical drugs such as steroids — cortisol, for example — systemic drugs and proteins such as insulin, as well as antigens for vaccination, among many other things,” says Carl Schoellhammer, an MIT graduate student in chemical engineering and one of the lead authors of a recent paper on the new system.

Ultrasound — sound waves with frequencies greater than the upper limit of human hearing — can increase skin permeability by lightly wearing away the top layer of the skin, an effect that is transient and pain-free.

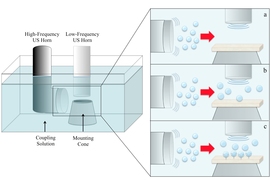

In a paper appearing in the Journal of Controlled Release, the research team found that applying two separate beams of ultrasound waves — one of low frequency and one of high frequency — can uniformly boost permeability across a region of skin more rapidly than using a single beam of ultrasound waves.

Senior authors of the paper are Daniel Blankschtein, the Herman P. Meissner ’29 Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT, and Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor at MIT. Other authors include Baris Polat, one of the lead authors and a former doctoral student in the Blankschtein and Langer groups, and Douglas Hart, a professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

Two frequencies are better than one

When ultrasound waves travel through a fluid, they create tiny bubbles that move chaotically. Once the bubbles reach a certain size, they become unstable and implode. Surrounding fluid rushes into the empty space, generating high-speed “microjets” of fluid that create microscopic abrasions on the skin. In this case, the fluid could be water or a liquid containing the drug to be delivered.

In recent years, researchers working to enhance transdermal drug delivery have focused on low-frequency ultrasound, because the high-frequency waves don’t have enough energy to make the bubbles pop. However, those systems usually produce abrasions in scattered, random spots across the treated area.

In the new study, the MIT team found that combining high and low frequencies offers better results. The high-frequency ultrasound waves generate additional bubbles, which are popped by the low-frequency waves. The high-frequency ultrasound waves also limit the lateral movement of the bubbles, keeping them contained in the desired treatment area and creating more uniform abrasion, Schoellhammer says.

“It’s a very innovative way to improve the technology, increasing the amount of drug that can be delivered through the skin and expanding the types of drugs that could be delivered this way,” says Samir Mitragotri, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of California at Santa Barbara, who was not part of the research team.

The researchers tested their new approach using pig skin and found that it boosted permeability much more than a single-frequency system. First, they delivered the ultrasound waves, then applied either glucose or inulin (a carbohydrate) to the treated skin. Glucose was absorbed 10 times better, and inulin four times better. “We think we can increase the enhancement of delivery even more by tweaking a few other things,” Schoellhammer says.

Noninvasive drug delivery

Such a system could be used to deliver any type of drug that is currently given by capsule, potentially increasing the dosage that can be administered. It could also be used to deliver drugs for skin conditions such as acne or psoriasis, or to enhance the activity of transdermal patches already in use, such as nicotine patches.

Ultrasound transdermal drug delivery could also offer a noninvasive way for diabetics to control their blood sugar levels, through short- or long-term delivery of insulin, the researchers say. Following ultrasound treatment, improved permeability can last up to 24 hours, allowing for delivery of insulin or other drugs over an extended period of time.

Such devices also hold potential for administering vaccines, according to the researchers. It has already been shown that injections into the skin can induce the type of immune response necessary for immunization, so vaccination by skin patch could be a needle-free, pain-free way to deliver vaccines. This would be especially beneficial in developing countries, since the training required to administer such patches would be less intensive than that needed to give injections. The Blankschtein and Langer groups are now pursuing this line of research.

They are also working on a prototype for a handheld ultrasound device, and on ways to boost skin permeability even more. Safety tests in animals would be needed before human tests can begin. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has previously approved single-frequency ultrasound transdermal systems based on Langer and Blankschtein’s work, so the researchers are hopeful that the improved system will also pass the safety tests.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.