It’s an obvious truism, but one that may soon be outdated: The problem with solar power is that sometimes the sun doesn’t shine.

Now a team at MIT and Harvard University has come up with an ingenious workaround — a material that can absorb the sun’s heat and store that energy in chemical form, ready to be released again on demand.

This solution is no solar-energy panacea: While it could produce electricity, it would be inefficient at doing so. But for applications where heat is the desired output — whether for heating buildings, cooking, or powering heat-based industrial processes — this could provide an opportunity for the expansion of solar power into new realms.

“It could change the game, since it makes the sun’s energy, in the form of heat, storable and distributable,” says Jeffrey Grossman, an associate professor of materials science and engineering, who is a co-author of a paper describing the new process in the journal Nature Chemistry. Timothy Kucharski, a postdoc at MIT and Harvard, is the paper’s lead author.

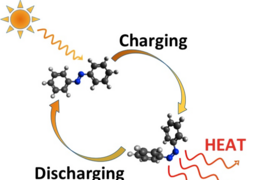

The principle is simple: Some molecules, known as photoswitches, can assume either of two different shapes, as if they had a hinge in the middle. Exposing them to sunlight causes them to absorb energy and jump from one configuration to the other, which is then stable for long periods of time.

But these photoswitches can be triggered to return to the other configuration by applying a small jolt of heat, light, or electricity — and when they relax, they give off heat. In effect, they behave as rechargeable thermal batteries: taking in energy from the sun, storing it indefinitely, and then releasing it on demand.

The new work is a follow-up to research by Grossman and his team three years ago, based on computer analysis. But translating that theoretical work into a practical material proved daunting: In order to reach the desired energy density — the amount of energy that can be stored in a given weight or volume of material — it is necessary to pack the molecules very close together, which proved to be more difficult than anticipated.

Grossman’s team tried attaching the molecules to carbon nanotubes (CNTs), but “it’s incredibly hard to get these molecules packed onto a CNT in that kind of close packing,” Kucharski says. But then they found a big surprise: Even though the best they could achieve was a packing density less than half of what their computer simulations showed they would need, the material nevertheless seemed to deliver the heat storage they were aiming for. Seeing a heat flow much greater than expected for the lower energy density prompted further investigation, Kucharski says.

After additional analysis, they realized that the photoswitching molecules, called azobenzene, protrude from the sides of the CNTs like the teeth of a comb. While the individual teeth were, indeed, twice as far apart as the researchers had hoped for, they were interleaved with azobenzene molecules attached to adjacent CNTs. The net result: The molecules were actually much closer to each other than expected.

The interactions between azobenzene molecules on neighboring CNTs make the material work, Kucharski says. While previous modeling showed that the packing of azobenzenes on the same CNT would provide only a 30 percent increase in energy storage, the experiments observed a 200 percent increase. New simulations confirmed that the effects of the packing between neighboring CNTs, as opposed to on a single CNT, explain the significantly larger enhancements.

This realization, Grossman says, opens up a wide range of possible materials for optimizing heat storage. Instead of searching for specific photoswitching molecules, the researchers can now explore various combinations of molecules and substrates. “Now we’re looking at whole new classes of solar thermal materials where you can enhance this interactivity,” he says.

Grossman says there are many applications where heat, not electricity, might be the desired outcome of solar power. For example, in large parts of the world the primary cooking fuel is wood or dung — which produces unhealthy indoor air pollution, and can contribute to deforestation. Solar cooking could alleviate that — and since people often cook while the sun isn’t out, being able to store heat for later use could be a big benefit.

Unlike fuels that are burned, this system uses material that can be continually reused. It produces no emissions and nothing gets consumed, Grossman says.

While further exploration of materials and manufacturing methods will be needed to create a practical system for production, Kucharski says, a commercial system is now “a big step closer.”

The adoption of carbon nanotubes to increase materials’ energy storage density is “clever,” says Yosuke Kanai, an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of North Carolina who was not involved in this work. He adds that the resulting increase in energy storage density “is surprising and remarkable.”

“This result provides additional motivation for researchers to design more and better photochromic compounds and composite materials that optimize the storage of solar energy in chemical bonds,” Kanai says.

The team also included MIT research scientist Nicola Ferralis, assistant professor of mechanical engineering Alexie Kolpak, and undergraduate Jennie Zheng, as well as Harvard professor Daniel Nocera. The work was supported by BP though the MIT Energy Initiative and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy.