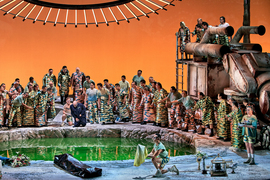

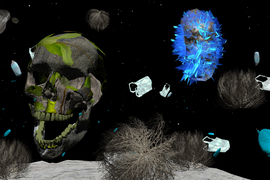

The world-famous Bayreuth Festival in Germany, annually centered around the works of composer Richard Wagner, launched this summer on July 25 with a production that has been making headlines. Director Jay Scheib, an MIT faculty member, has created a version of Wagner’s celebrated opera “Parsifal” that is set in an apocalyptic future (rather than the original Medieval past), and uses augmented reality headset technology for a portion of the audience, among other visual effects. People using the headsets see hundreds of additional visuals, from fast-moving clouds to arrows being shot at them. The AR portion of the production was developed through a team led by designer and MIT Technical Instructor Joshua Higgason.

The new “Parsifal” has engendered extensive media attention and discussion among opera followers and the viewing public. Five years in the making, it was developed with the encouragement of Bayreuth Festival general manager Katharina Wagner, Richard Wagner’s great-granddaughter. The production runs until Aug. 27, and can also be streamed on Stage+. Scheib, the Class of 1949 Professor in MIT’s Music and Theater Arts program, recently talked to MIT News about the project from Bayreuth.

Q: Your production of “Parsifal” led off this year’s entire Bayreuth festival. How’s it going?

A: From my point of view it’s going quite swimmingly. The leading German opera critics and the audiences have been super-supportive and Bayreuth makes it possible for a work to evolve … Given the complexity of the technical challenge of making an AR project function in an opera house, the bar was so high, it was a difficult challenge, and we’re really happy we found a way forward, a way to make it work, and a way to make it fit into an artistic process. I feel great.

Q: You offer a new interpretation of “Parsifal,” and a new setting for it. What is it, and why did you choose to interpret it this way?

A: One of the main themes in “Parsifal” is that the long-time king of this holy grail cult is wounded, and his wound will not heal. [With that in mind], we looked at what the world was like when the opera premiered in the late 19th century, around the time of what was known as the Great African Scramble, when Europe re-drew the map of Africa, largely based on resources, including mineral resources.

Cobalt remains [the focus of] dirty mining practices in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and is a requirement for a lot of our electronic objects, in particular batteries. There are also these massive copper deposits discovered under a Buddhist temple in Afghanistan, and lithium under a sacred site in Nevada. We face an intense challenge in climate change, and the predictions are not good. Some of our solutions like electric cars require these materials, so they’re only solutions for some people, while others suffer [where minerals are being mined]. We started thinking about how wounds never heal, and when the prospect of creating a better world opens new wounds in other communities. … That became a theme. It also comes out of the time when we were making it, when Covid happened and George Floyd was murdered, which created an opportunity in the U.S. to start speaking very openly about wounds that have not healed.

We set it in a largely post-human environment, where we didn’t succeed, and everything has collapsed. In the third act, there’s derelict mining equipment, and the holy water is this energy-giving force, but in fact it’s this lithium-ion pool, which gives us energy and then poisons us. That’s the theme we created.

Q: What were your goals about integrating the AR technology into the opera, and how did you achieve that?

A: First, I was working with my collaborator Joshua Higgason. No one had ever really done this before, so we just started researching whether it was possible. And most of the people we talked to said, “Don’t do it. It’s just not going to work.” Having always been a daredevil at heart, I was like, “Oh, come on, we can figure this out.”

We were diligent in exploring the possibilities. We made multiple trips to Bayreuth and made these milimeter-accurate laser scans of the auditorium and the stage. We built a variety of models to see how to make AR work in a large environment, where 2,000 headsets could respond simultaneously. We built a team of animators and developers and programmers and designers, from Portugal to Cambridge to New York to Hungary, the UK, and a group in Germany. Josh led this team, and they got after it, but it took us the better part of two years to make it possible for an audience, some of whom don’t really use smartphones, to put on an AR headset and have it just work.

I can’t even believe we did this. But it’s working.

Q: In opera there’s hopefully a productive tension between tradition and innovation. How do you think about that when it comes to Wagner at Bayreuth?

A: Innovation is the tradition at Bayreuth. Musically and scenographically. “Parsifal” was composed for this particular opera house, and I’m incredibly respectful of what this event is made for. We are trying to create a balanced and unified experience, between the scenic design and the AR and the lighting and the costume design, and create perfect moments of convergence where you really lose yourself in the environment. I believe wholly in the production and the performers are extraordinary. Truly, truly, truly extraordinary.

Q: People have been focused on the issue of bringing AR to Bayreuth, but what has Bayreuth brought to you as a director?

A: Working in Bayreuth has been an incredible experience. The level of intellectual integrity among the technicians is extraordinary. The amount of care and patience and curiosity and expertise in Bayreuth is off the charts. This community of artists is the greatest. … People come here because it’s an incredible meeting of the minds, and for that I’m immensely filled with gratitude every day I come into the rehearsal room. The conductor, Pablo Heras-Casado, and I have been working on this for several years. And the music is still first. We’re setting up technology not to overtake the music, but to support it, and visually amplify it.

It must be said that Katharina Wagner has been one of the most powerfully supportive artistic directors I have ever worked with. I find it inspiring to witness her tenacity and vision in seeing all of this through, despite the hurdles. It’s been a great collaboration. That’s the essence: great collaboration.

This work was supported, in part, by an MIT.nano Immersion Lab Gaming Program seed grant, and was developed using capabilities in the Immersion Lab. The project was also funded, in part, by a grant from the MIT Center for Art, Science, and Technology.